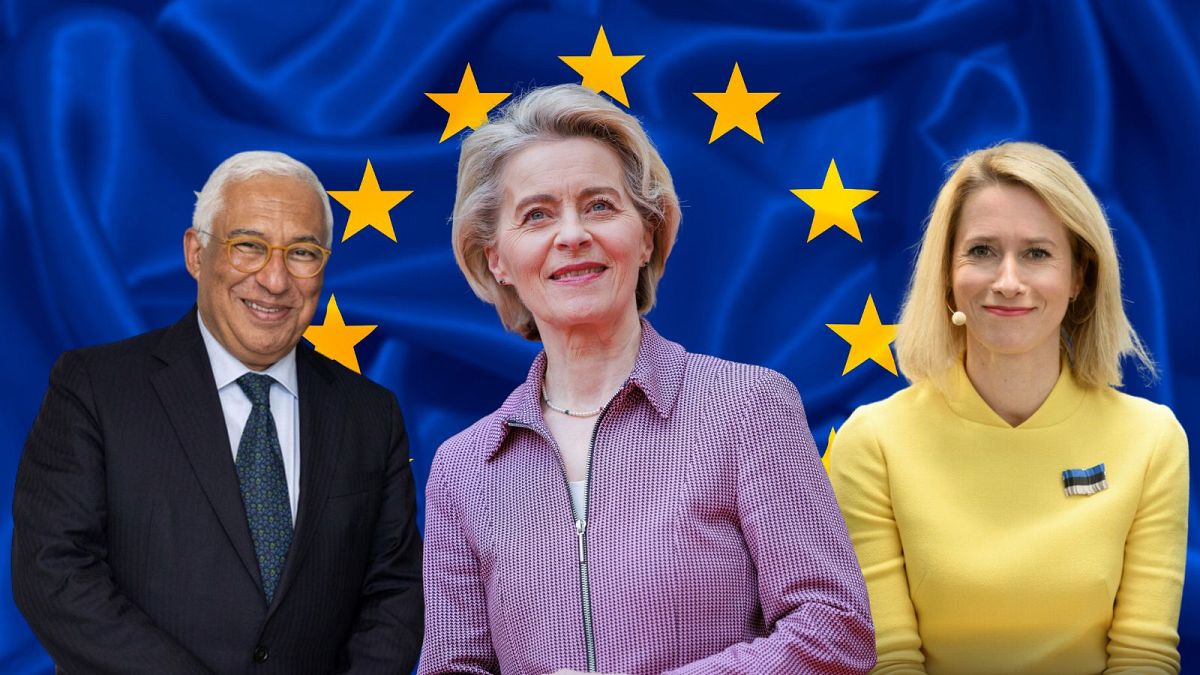

Ursula von der Leyen, António Costa and Kaja Kallas have been tipped to lead the European Union in the next five years.

White smoke in Brussels.

The 27 leaders of the European Union have agreed on the bloc’s political leadership for the next five years: Ursula von der Leyen as president of the European Commission, António Costa as president of the European Council, and Kaja Kallas as the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

Leaders on Thursday also approved the Strategic Agenda, a document with broad brushstrokes of ambitions that is meant to guide the future work of the three appointees.

Von der Leyen and Kallas’s nominations are not final and still require confirmation by the European Parliament. By contrast, Costa, a former prime minister of Portugal, is automatically elected by his former peers. He will take office on 1 December.

“It is with a strong sense of mission that I will take up the responsibility of being the next President of the European Council,” Costa said, thanking his socialist family and the Portuguese government for their backing. “I will be fully committed to promoting unity between all 27 Member States and focused on putting on track the Strategic Agenda.”

“This is an enormous responsibility at this moment of geopolitical tensions,” Kallas said in a statement, promising to work “with pleasure” with both von der Leyen and Costa. “I will be at the service of our common interests,” she added. “Europe should be a place where people are free, safe and prosperous.”

Party negotiators had preemptively sealed the three-pronged deal during a call on Tuesday and tabled their proposal on Thursday evening. After a debate among all heads of state and government, the accord received the formal blessing.

The talks between the centrist parties had angered those left on the sidelines, most notably Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who lashed out at the “surreal” way in which the top-jobs package was assembled. Meloni, who rules the bloc’s third-largest economy, called for greater inclusion and deeper discussions.

“It seems to me that, so far, there’s been an unwillingness to account for the message delivered by citizens at the ballot box,” Meloni said on the eve of the summit.

Hungary’s Viktor Orbán was more scathing, calling the deal “shameful.”

Their public grievances contrasted with the apparent coolness of other dignitaries, such as Germany’s Olaf Scholz and France’s Emmanuel Macron, who were intent on wrapping up the process in a swift, uncomplicated manner.

“We are living in difficult times. We are faced with major challenges, not least Russia’s terrible war of aggression against Ukraine. It is therefore important that Europe prepares itself now for the tasks that need to be tackled,” Scholz said upon arrival.

Diplomats in Brussels were concerned that, due to the volatile geopolitical environment surrounding the bloc, the image of leaders haggling over well-paid positions for hours on end would seem out of touch.

These worries, coupled with a lack of credible alternatives, made the negotiations easier and helped positions coalesce around the three names.

“Democracy is not only about blocking, democracy is about who wants to work together, and those three groups are willing to work together to the benefit of all Europeans,” said Belgium’s Alexander De Croo, rebuking Meloni’s criticism.

“What we need in the next five years is political stability and being able to act fast.”

In the end, Meloni voted against Costa and Kallas, and abstained on von der Leyen, several diplomats told Euronews, a largely symbolic move to express her displeasure. For his part, Orbán voted against von der Leyen, abstained on Kallas and supported Costa.

For those following European politics, the chosen ones are familiar faces.

The Commission presidency goes to the incumbent, Ursula von der Leyen, the Spitzenkandidat (lead candidate) of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP).

Since announcing her re-election bid in February, von der Leyen, the first woman to captain the executive, had been the indisputable frontrunner thanks to her high political profile, built up while weathering the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war.

During the campaign, she infuriated progressives when she made overtures to Meloni’s hard right. But the EPP’s comfortable victory in the June elections, with 188 MEPs, lessened Rome’s importance in the equation and allowed her to change her tune. Von der Leyen has promised to build a strong centrist coalition to support her next term.

At a distant second came the Socialists & Democrats (S&D), with 136 seats. The family will see one of its most recognisable faces, former Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa, take the reins of the European Council, succeeding Charles Michel.

Although the Council presidency lacks legislative powers, the back-to-back succession of global crises that have hit the bloc in the last five years has increased the job’s political relevance and media exposure, making it a coveted prize for the centre-left.

Costa’s ascendancy, however, comes with a question mark: his stay in power was cut short in November 2023, when he resigned after several members of his cabinet were accused of corruption and influence peddling in the concession of lithium mining, green hydrogen and data centre projects. Costa has not been formally charged but his exact participation in the irregular deals has not yet been clarified. He denies any wrongdoing.

Meanwhile, the liberals of Renew Europe, who fell hard from 102 to 75 seats, have secured the position of High Representative for Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, a leading figure in the bloc’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Kallas was initially considered too outspoken and hawkish for the office, which is supposed to act as the common voice of the 27 member states vis-à-vis the international community. But concerns around her suitability gradually dwindled and her name, previously linked to the NATO secretary general job, was greenlighted.

Despite its prominence, the High Representative is inherently constrained by the principle of unanimity that rules the EU’s foreign policy. If confirmed by the Parliament, Kallas will replace Josep Borrell, who has often been accused of going off-script.

With von der Leyen, Costa and Kallas picked for the top jobs, EU leaders ensure the distribution reflects the bloc’s political and geographical diversity and maintains gender balance. Additionally, Costa, whose father was half French-Mozambican and half Indian, is set to become the first non-white person to occupy a top job in the bloc’s history.

The selection can be seen as recognition of centrist parties, who held their ground in the elections and defied ominous predictions of a far-right surge. Von der Leyen is already negotiating with the Socialists and Liberals to design a common programme.

This article has been updated with more information.