The two-day summit will focus on the EU top jobs, the Strategic Agenda for the next five years, military support for Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war.

The 27 leaders of the European Union are due to meet on Thursday to give the final push to a deal that will allocate the bloc’s top jobs for the next five years.

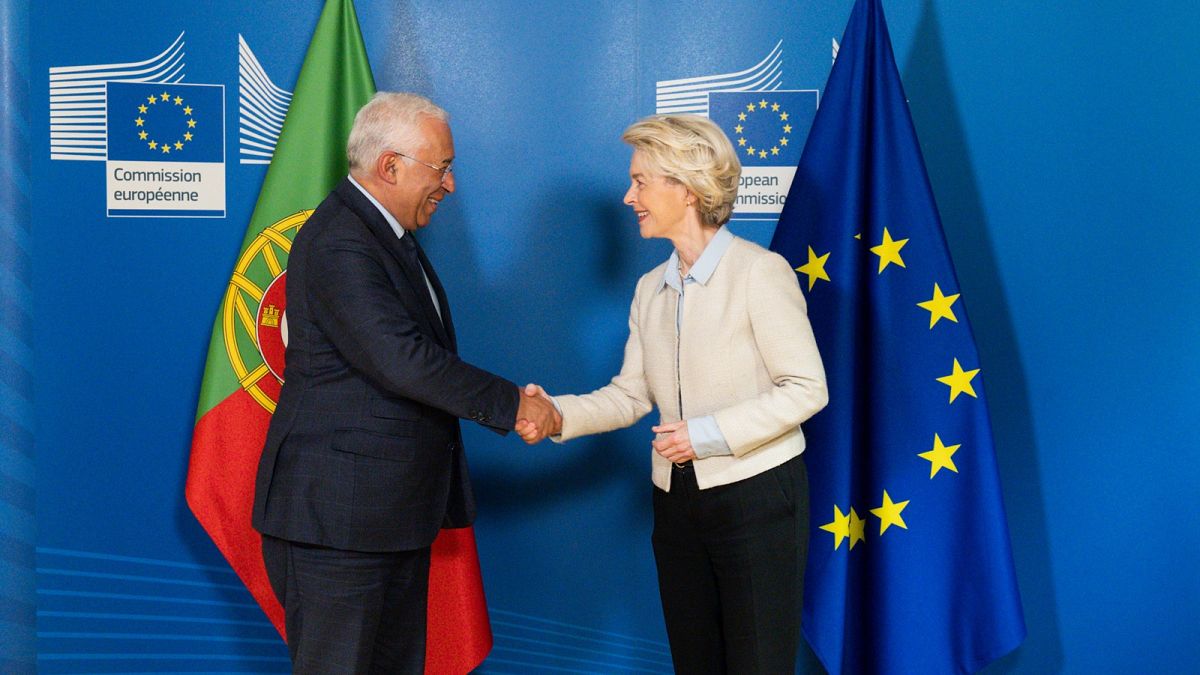

The names on the table are well-known by now: Ursula von der Leyen as president of the European Commission, António Costa as president of the European Council and Kaja Kallas as High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

The trio has been put together based on their proven political credentials on the European stage – and also a lack of credible alternatives who could act as Plan B.

Following a failed attempt last week, the six negotiators of the main centrist parties –Poland’s Donald Tusk, Greece’s Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Germany’s Olaf Scholz, Spain’s Pedro Sánchez, France’s Emmanuel Macron and the Netherlands’ Mark Rutte – held a phone call earlier this week and reconfirmed the selection.

Crucially, the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP), the big winner of the elections, dropped its demand to have one of its ranks replace Costa in the European Council after his 2.5-year term. This request angered the Socialists, who have bet big on Costa despite the judicial woes surrounding the former Portuguese prime minister.

Negotiators “agreed to back the established practice of continuity and endorse the elected candidate for the entire legislative cycle,” a diplomat said after the joint call.

This means the EPP will retain control of the Commission, the bloc’s most powerful institution, and the Socialists will take the reins of the Council, which hosts high-level meetings of leaders. Meanwhile, the liberals of Renew Europe, who suffered painful losses in the election, will be given the High Representative, the EU’s top diplomat.

For Kallas, the assignment is a vindication after she was sidelined to be the next Secretary General of NATO due to her hawkish stance on Russia. The same reason was initially invoked against her possible candidacy for High Representative but the worries gradually disappeared. Geography helped her case: Eastern Europeans have long insisted one of the three top jobs should go to one of their own, making Kallas the ideal fit.

Still, the VDL-Costa-Kallas deal needs to be endorsed by the 27 leaders before it becomes a reality. At the same time, the heads of state and government will agree on a Strategic Agenda that defines the main priorities for the upcoming mandate.

If eventually appointed, von der Leyen and Kallas will have to undergo a public hearing and confirmation vote at the European Parliament.

Strictly speaking, the decision on the top jobs is taken by a reinforced qualified majority, meaning 20 member states representing at least 65% of the bloc’s population. As the EPP, the Socialists and the Liberals occupy most of the seats in the Council, the provisional agreement has the necessary endorsements to be formally blessed.

However, given the political sensitivity of the decision, which will have ramifications for the next five years, the Council prefers to distribute top jobs through consensus, having as many votes in favour as possible.

There is one key vote that all guests will be eagerly awaiting: Giorgia Meloni’s.

The Italian premier, who hails from the hard-right European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, has been excluded from the talks between the three centrist parties, which she strongly resents. Mitsotakis was tasked with informing Meloni about the outcome of the joint call but, according to La Stampa, she never picked up the phone.

“No true democrat who believes in popular sovereignty can in his or her heart consider it acceptable that in Europe there was an attempt to negotiate on top positions even before the people went to the polls,” Meloni told the Italian Parliament on Wednesday.

The draft agreement, she said, overrides the logic of consensus because it does not include “those on the opposite political side and those of nations considered too small to be worthy to sit at the tables that count.”

Czechia’s Petr Fiala, another ECR member, and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, who has been politically unaffiliated for years, have also voiced their discontent and urged greater inclusion in the negotiations.

Orbán is vehemently opposed to von der Leyen, who has partially frozen the country’s recovery and cohesion funds in response to its continued democratic backsliding, but has no objections to Costa and Kallas.

Diplomats and officials acknowledge that a proper discussion needs to happen among all leaders to avoid the impression of a “pre-cooked” deal sailing through. The expectation is for the agreement to be reached sometime on Thursday, as President Macron is eager to return to France to resume the electoral campaign ahead of Sunday’s first round of the snap legislative elections he called following his party’s stringing defeat in the Euroepan elections.

“Our aim will be to have the largest number of people on board,” said a senior EU official, noting that Meloni has the option to abstain rather than vote against.

“Sometimes you need to asses why they (leaders) abstain. One was forced to abstain last time,” the official added, referring to Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose coalition asked her to abstain in 2019 when von der Leyen was surprisingly elevated.

As the hard right has virtually no chance of snatching a top job, those on the sidelines are eyeing important portfolios in the next European Commission as compensation.

Italy, in particular, has lofty ambitions.

“We want to have a Vice-President in the European Commission. A strong Commissioner to promote good policies in favour of industry and agriculture,” said Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani, giving a hint of what Rome is after.

Meloni might use Thursday’s meeting to pitch her requests to von der Leyen on a bilateral basis. But a senior diplomat said this “shouldn’t happen that way.”

“Von der Leyen will have to decide on her own when she has all candidates to form the next Commission,” the diplomat said.

Besides the top jobs, the two-day summit will address other issues high on the agenda, such as military support for Ukraine (€6.6 billion of which remains blocked by Hungary), the situation in Georgia, and the Israel-Hamas war, with a focus on Lebanon.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy will make a brief, in-person appearance at the Council to sign the security commitments between the EU and Ukraine.

The summit will mark the last intervention of Mark Rutte after 14 uninterrupted years as Dutch prime minister. He will soon become the next Secretary General of NATO.